Abstract

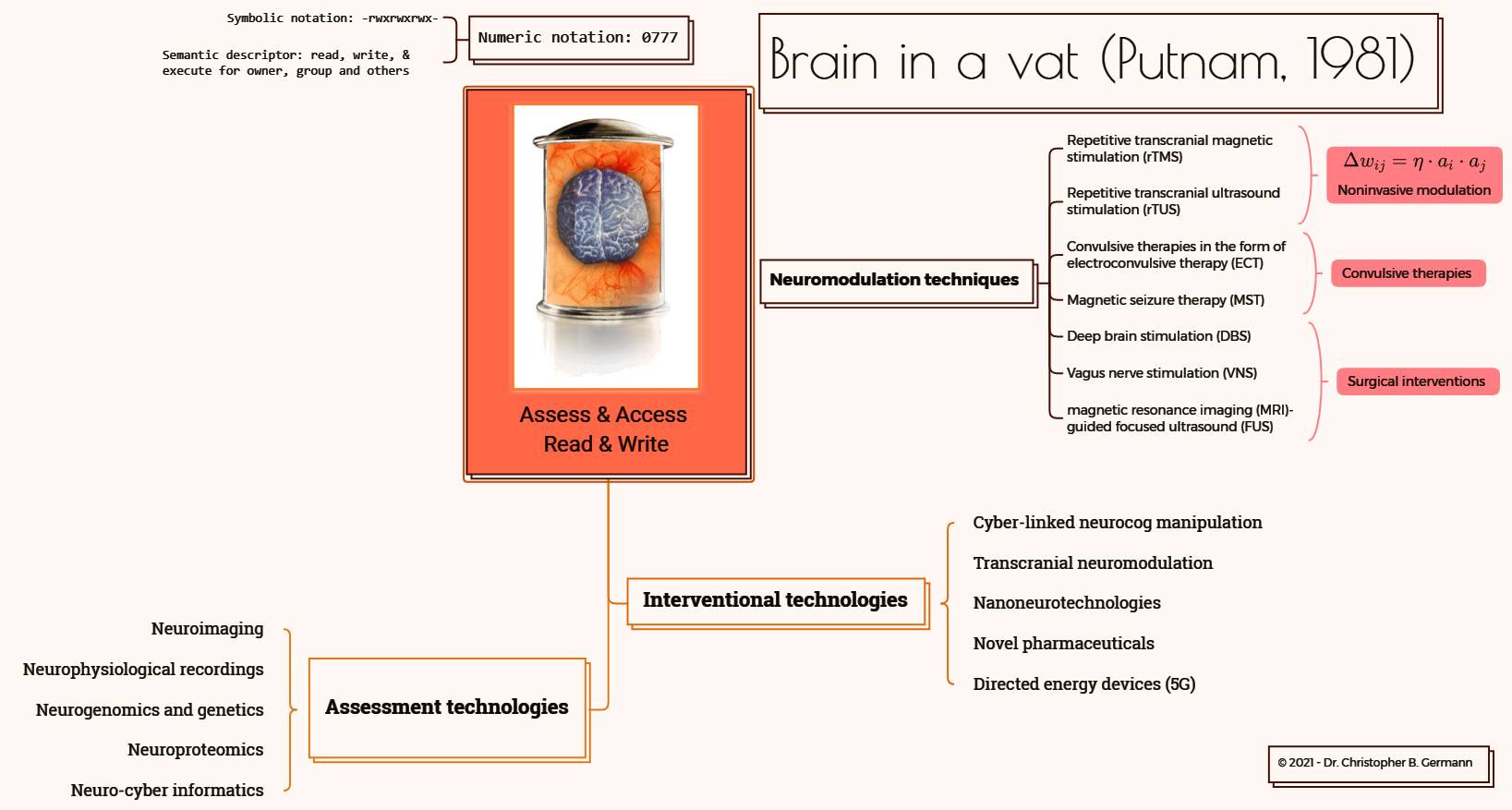

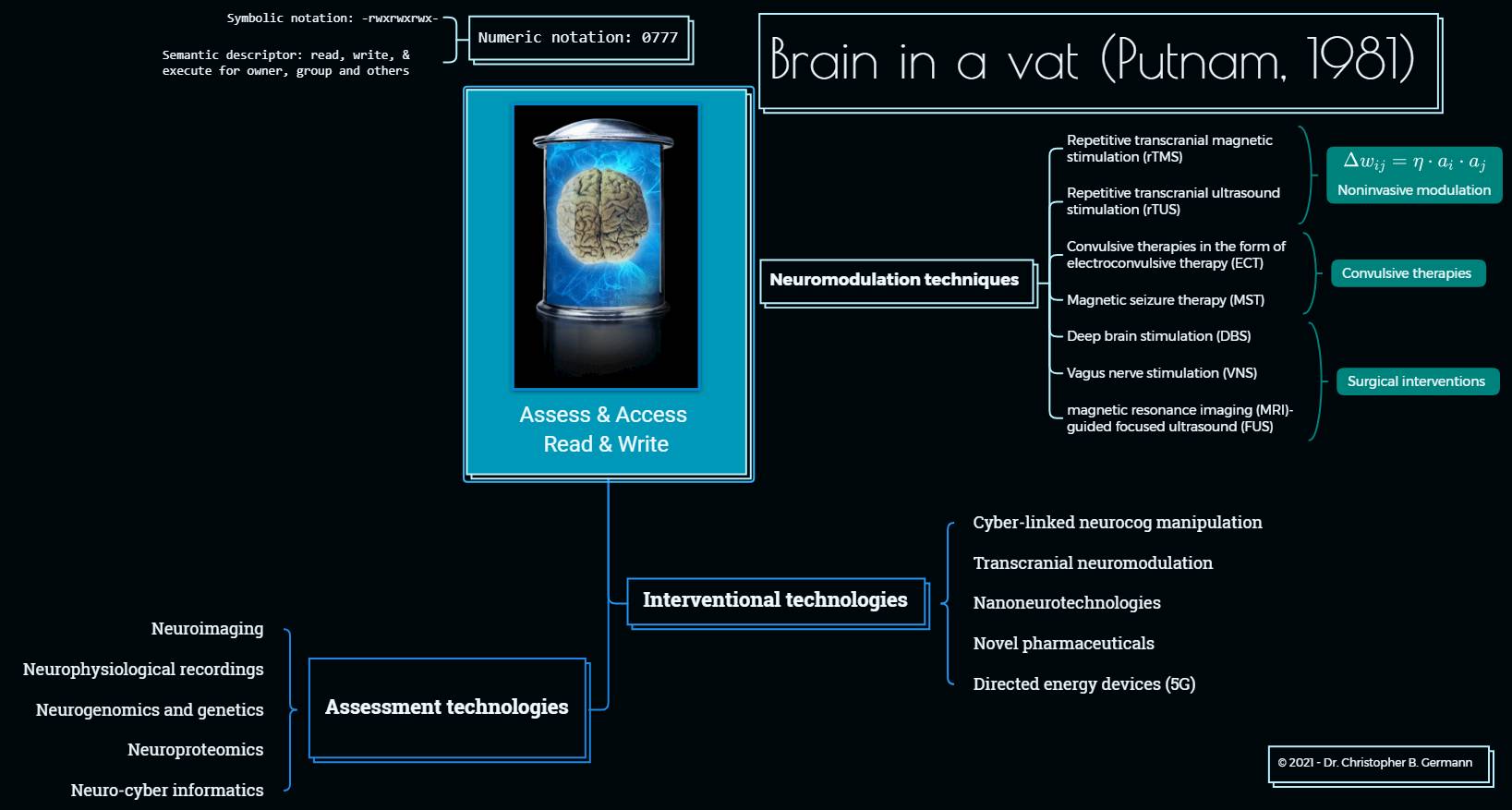

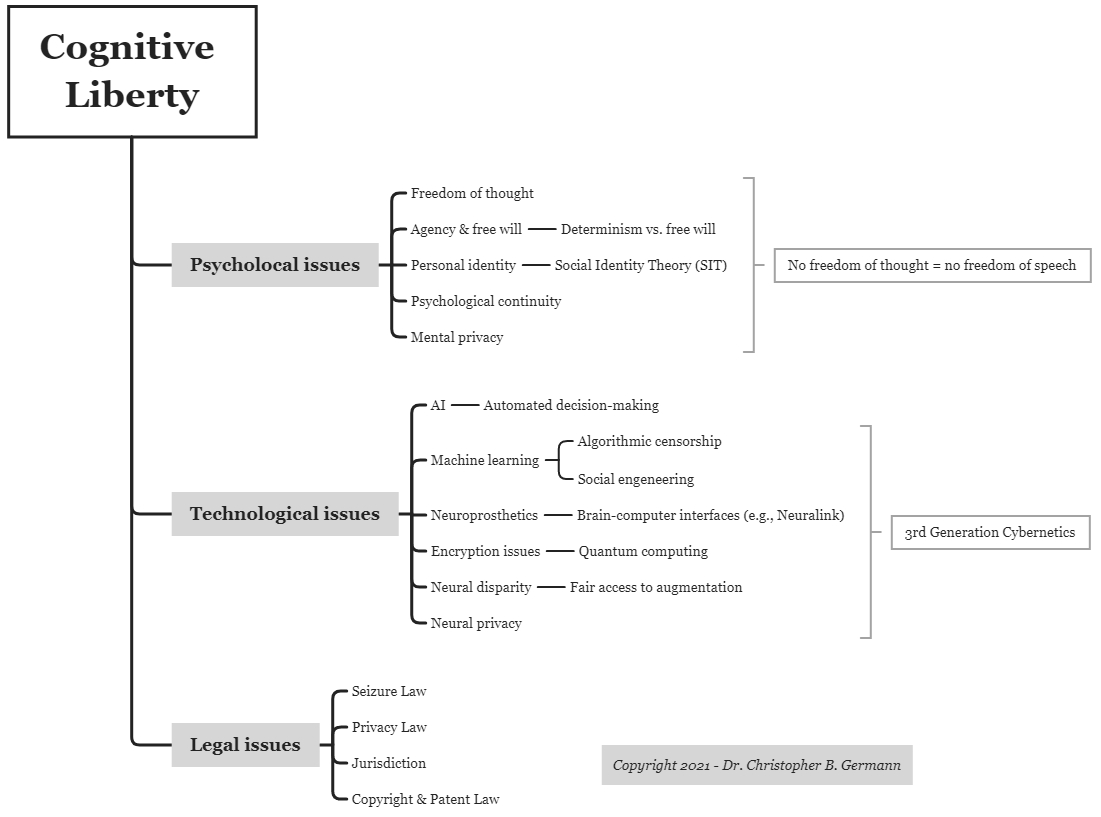

The rise of neurotechnologies, especially in combination with artificial intelligence (AI)-based methods for brain data analytics, has given rise to concerns around the protection of mental privacy, mental integrity and cognitive liberty – often framed as “neurorights” in ethical, legal, and policy discussions. Several states are now looking at including neurorights into their constitutional legal frameworks, and international institutions and organizations, such as UNESCO and the Council of Europe, are taking an active interest in developing international policy and governance guidelines on this issue. However, in many discussions of neurorights the philosophical assumptions, ethical frames of reference and legal interpretation are either not made explicit or conflict with each other. The aim of this multidisciplinary work is to provide conceptual, ethical, and legal foundations that allow for facilitating a common minimalist conceptual understanding of mental privacy, mental integrity, and cognitive liberty to facilitate scholarly, legal, and policy discussions.

Further References

For example, Ienca, M, Andorno, R. Towards new human rights in the age of neuroscience and neurotechnology. Life Sciences, Society and Policy 2017;13(1):5CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed; Sommaggio P, Mazzocca M, Gerola A, Ferro F. Cognitive liberty. A first step towards a human neuro-rights declaration. BioLaw Journal—Rivista di BioDiritto 2017;3:27–45; McCarthy-Jones S. The autonomous mind: The right to freedom of thought in the twenty-first century. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2019;2:1–7; Bublitz, J-C. The nascent right to psychological integrity and mental self-determination. In: von Arnauld, A, der Decken, K, Susi, M, eds. The Cambridge Handbook of New Human Rights: Recognition, Novelty, Rhetoric. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2020:387–403 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Michalowski, S. Critical reflections on the need for a right to mental self-determination. In von Arnauld, A, der Decken, K, Susi, M, eds. The Cambridge Handbook of New Human Rights: Recognition, Novelty, Rhetoric. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2020:404–12CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Alegre S. Rethinking freedom of thought for the 21st century, European Human Rights Law Review 2017;(3):221–33; Ligthart, S. Freedom of thought in Europe: Do advances in “brain-reading” technology call for revision?, Journal of Law and the Biosciences 2020;7(1):lsaa048CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed; Ligthart, S, Douglas, T, Bublitz, C, Kooijmans, T, Meynen, G. Forensic brain-reading and mental privacy in European Human Rights Law: Foundations and challenges. Neuroethics 2021;14(2):191–203 CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.2

Report on Respecting, Protecting and Fulfilling the Right to Freedom of Thought, to the 76th Session of the General Assembly, October 2021; United Nations, Our Common Agenda—Report of the Secretary-General, New York 2021, para 35.

3

Declaration of the Interamerican Juridical Committee on Neuroscience, Neurotechnologies and Human Rights: New Legal Challenges for the Americas, CJI/DEC. 01 (XCIX-O/21, August 11, 2021).

4

Committee on Bioethics of the Council of Europe. Strategic Action Plan on Human Rights and Technologies in Biomedicine (2020–2025), Adopted by the Committee on Bioethics (DH-BIO) at its 16th meeting (19–21 November 2019).

5

Report of the International Bioethics Committee of UNESCO. Ethical Issues of Neurotechnology, SHS/BIO/IBC28/2021/3Rev., Paris, France: UNESCO, 15 December 2021. See also Navarro MS, Dura-Bernal S, Gulotta CM, Stark C (eds.). The Risks and Challenges of Neurotechnologies for Human Rights. Paris, France; Milan, Italy; New York, NY: UNESCO; University of Milan-Bicocca – Department of Business and Law; State University of New York (SUNY) Downstate; 2023.

6

OECD. Recommendation on Responsible Innovation in Neurotechnology. Adopted by the OECD Council on 11 December 2019.

7

See note 4, Committee on Bioethics of the Council of Europe 2019.

8

Yuste, R, Goering, S, Arcas, BAY, Bi, G, Carmena, JM, Carter, A, et al. Four ethical priorities for neurotechnologies and AI. Nature 2017;551(7679):159–63CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed; Goering, S, Klein, E, Specker Sullivan, L, Wexler, A, , Agüera Y Arcas, B, Bi, G, et al. Recommendations for responsible development and application of neurotechnologies. Neuroethics 2021;14(3):365–86CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

9

Seaman JA. Your brain on lies: Deception detection in court. In: The Routledge Handbook of Neuroethics. New York, NY: Routledge; 2017; Farahany N. Searching secrets. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 2012;160(5):1239; Farahany N. Incriminating thoughts. Stanford Law Review 2012;64:351–408; Neurolaw: Advances in neuroscience, justice, and security. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan; 2021; McCay A. Neurotechnology, law and the legal profession, horizon report for the law society. The Law Society 2022; available at www.lawsociety.org.uk/topics/research/how-will-brain-monitoring-technology-influence-the-practice-of-law. Jotterand F. Punishment, responsibility, and brain interventions. In: Jotterand F, ed. The Unfit Brain and the Limits of Moral Bioenhancement. Singapore: Springer; 2022:171–92.

10

Gilbert, F, Dodds, S. Is there anything wrong with using AI Implantable brain devices to prevent convicted offenders from reoffending? In: Vincent, NA, Nadelhoffer, T, McCay, A, eds. Neurointerventions and the Law: Regulating Human Mental Capacity. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2020 Google Scholar; Birks, D, Douglas, T, Birks, D, Douglas, T (eds.), Treatment for Crime: Philosophical Essays on Neurointerventions in Criminal Justice. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2018 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; See note 9, McCay 2022.

11

See note 1, Ienca, Andorno 2017, at 5; Genser J, Hermann S, Yuste R. International Human Rights Protection Gaps in the Age of Neurotechnology, report of the NeuroRights Foundation; 2022.

12

For some critical notes, see Zúñiga-Fajuri A, Miranda LV, Miralles DZ, Venegas RS. Chapter seven—Neurorights in Chile: Between neuroscience and legal science. In Hevia M, ed. Developments in Neuroethics and Bioethics. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2021:165–79; Fins JJ. The unintended consequences of Chile’s neurorights constitutional reform: Moving beyond negative rights to capabilities. Neuroethics 2022;15(3):26.

13

Report on Respecting, Protecting and Fulfilling the Right to Freedom of Thought, to the 76th Session of the General Assembly expected in July 2021; Declaration of the Interamerican Juridical Committee on Neuroscience, Neurotechnologies and Human Rights: New Legal Challenges for the Americas, CJI/DEC. 01 (XCIX-O/21, August 11, 2021; Ienca M. Common human rights challenges raised by different applications of neurotechnologies in the biomedical field, 2021; See note 4, Committee on Bioethics of the Council of Europe 2019.

14

See note 5, Navarro 2022.

15

As is often the case in interdisciplinary work, not all authors that contributed to the discussions and the resulting paper agree with every point made in the paper. We have made substantial efforts in harmonizing views and interpretations but also want to acknowledge the reality of “reasonable disagreement”.

16

It might be argued that drawing a distinction between bodily and mental integrity implicitly endorses a form of dualism between the body (including the brain) and the mind. To avoid this risk, some have proposed recognising a single right to “identity integrity”. However, since the rights to bodily and mental integrity are widely used in the academic literature and acknowledged in the law, such as by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, we will stick to this terminology in this paper. In adopting this terminology, we do not mean to endorse dualism.

17

Ienca, M, Haselager, P, Emanuel, EJ. Brain leaks and consumer neurotechnology. Nature Biotechnology 2018;36(9):805–10CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed; Williamson, B. Brain data: Scanning, scraping and sculpting the plastic learning brain through neurotechnology. Postdigital Science and Education 2019;1(1):65–86 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Kellmeyer, P. Big brain data: On the responsible use of brain data from clinical and consumer-directed neurotechnological devices. Neuroethics 2021;14(1):83–98 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

18

Ligthart S, Toor D van, Kooijmans T, Douglas T, Meynen G (eds.), Neurolaw: Advances in Neuroscience, Justice & Security. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan; 2021. See note 10, Birks et al. 2018.

19

Ienca, M, Jotterand, F, Elger, BS. From healthcare to warfare and reverse: How should we regulate dual-use neurotechnology? Neuron 2018;97(2):269–74CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

20

Roc, A, Pillette, L, Mladenovic, J, Benaroch, C, N’Kaoua, B, Jeunet, C, et al. A review of user training methods in brain computer interfaces based on mental tasks. Journal of Neural Engineering 2021;18(1): 1–32CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed;. Krol LR, Haselager P, Zander TO. Cognitive and affective probing: A tutorial and review of active learning for neuroadaptive technology. Journal of Neural Engineering 2020;17:1–15.

21

Delfin C, Krona H, Andiné P, Ryding E, Wallinius M, Hofvander B. Prediction of recidivism in a long-term follow-up of forensic psychiatric patients: Incremental effects of neuroimaging data. PLOS ONE 2019;14(5):e0217127; Aharoni, E, Vincent, GM, Harenski, CL, Calhoun, VD, Sinnott-Armstrong, W, Gazzaniga, MS, et al. Neuroprediction of future rearrest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013;110(15):6223–28CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

22

Farah, MJ, Hutchinson, JB, Phelps, EA, Wagner, AD. Functional MRI-based lie detection: Scientific and societal challenges. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2014;15(2):123–31CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

23

Krauss, JK, Lipsman, N, Aziz, T, Boutet, A, Brown, P, Chang, JW, et al. Technology of deep brain stimulation: Current status and future directions. Nature Reviews Neurology 2021;17(2):75–87 CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

24

De Risio, L, Borgi, M, Pettorruso, M, Miuli, A, Ottomana, AM, Sociali, A, et al. Recovering from depression with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Translational Psychiatry 2020;10(1):1–19 CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

25

Bouthour, W, Mégevand, P, Donoghue, J, Lüscher, C, Birbaumer, N, Krack, P. Biomarkers for closed-loop deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease and beyond. Nature Reviews Neurology 2019;15(6):343–52CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed; Holmen, SJ, Ryberg, J. Interventionist advisory brain devices, aggression, and crime prevention. Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics 2021;8:1–22 Google Scholar.

26

Mashat, MEM, Li, G, Zhang, D. Human-to-human closed-loop control based on brain-to-brain interface and muscle-to-muscle interface. Scientific Reports 2017;7(1):11001 CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed. For an overview see also: Kellmeyer, P. Artificial intelligence in basic and clinical neuroscience: Opportunities and ethical challenges. Neuroforum 2019;25:241–50CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

27

Jones, EG, Mendell, LM. Assessing the decade of the brain. Science 1999;284(5415):739–9CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

28

Human Brain Project; available at www.humanbrainproject.eu/en/ (last accessed 22 Mar 2023); NIH BRAIN Initative; available at braininitiative.nih.gov/ (last accessed 22 Mar 2023).

29

The term was coined in a series of essays by Boire RG. On cognitive liberty. Journal of Cognitive Liberties; available at (www.cognitiveliberty.org/ccle1/1jcl/1jcl (last accessed 22 Mar 2023).

30

See note 12, Ienca 2021.

31

In our discussion here, we will refer to specific “neurorights” as “human rights” if they are conceptualized (or discussed) within an international and universal context (e.g., in discussions at the level of the UN).

32

Kellmeyer P. “Neurorights”: A human rights–based approach for governing neurotechnologies. In: Mueller O, Kellmeyer P, Voeneky S, Burgard W, eds. The Cambridge Handbook of Responsible Artificial Intelligence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2022:412–26; See note 1, Ienca, Andorno 2017; See note 1, Sommaggio et al. 2017; See note 11, NeuroRights Foundation 2022.

33

Bublitz, JC. Novel neurorights: From nonsense to substance. Neuroethics 2022;15(1):7CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed; Bublitz, JC. Freedom of thought in the age of neuroscience: A plea and a proposal for the renaissance of a forgotten fundamental right. ARSP: Archiv für Rechts- und Sozialphilosophie/Archives for Philosophy of Law and Social Philosophy 2014;100(1):1–25 Google Scholar; Ligthart S. Coercive Brain-Reading in Criminal Justice: An Analysis of European Human Rights Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2022; Hertz N. Neurorights—Do we need new human rights? A reconsideration of the right to freedom of thought. Neuroethics 2022;16(1):5; See note 1, McCarthy-Jones 2019; See note 1, Alegre 2017.

34

Rainey, S, McGillivray, K, Akintoye, S, Fothergill, T, Bublitz, C, Stahl, B. Is the European data protection regulation sufficient to deal with emerging data concerns relating to neurotechnology? Journal of Law and the Biosciences 2020;7(1):lsaa051CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed; See note 1, Ligthart et al. 2021.

35

See note 1, Michalowski 2020; see note 1, Ligthart 2020; see note 12, Zúñiga-Fajuri et al. 2021.

36

Douglas, T, Forsberg, L. Three rationales for a legal right to mental integrity. In: Ligthart, S, van Toor, D, Kooijmans, T, Douglas, T, Meynen, G, eds. Neurolaw: Advances in Neuroscience, Justice & Security. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021:179–201 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Lavazza A. freedom of thought and mental integrity: The moral requirements for any neural prosthesis. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2018;12:1–10; see note 8, Goering et al. 2021; Mecacci, G, Haselager, P. Identifying criteria for the evaluation of the implications of brain reading for mental privacy. science and engineering. Ethics 2019;25:443–61Google Scholar; Germani, F, Kellmeyer, P, Wäscher, S, Biller-Andorno, N. Engineering minds? Ethical considerations on biotechnological approaches to mental health, well-being, and human flourishing. Trends in Biotechnology 2021;39:1111–3CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

37

Criticism of the implementation of legal language for moral rights addresses structural problems such as the integration of a vertical view typical of human rights jurisprudence, which runs counter to the traditional horizontal view in ethical reasoning. Legal language too often implies the violation of rights, whereas ethical language presupposes reciprocal dialogue between actors without implying that rights have been previously violated or duties not fulfilled. Sperling D. Law and bioethics: A rights-based relationship and its troubling implications. In: Freeman M, ed. Law and Bioethics: Current Legal Issues, Vol. 11. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. Moreover, ethical choices can be made between two legally acceptable solutions, which helps to ground the reasoning about which ethical and moral concepts should be condensed into law. Additionally, in order to do justice to ethical decisions, it is not always enough to meet legal standards. See Sperling 2008, at 65, 71.

38

Henceforth, our use of “rights” means “legal rights.”

39

It may be the case that dualist ideas have a more pervasive influence on legal systems. See Fox, D, Stein, A. Dualism and doctrine. Indiana Law Journal 2015;90(3):975 Google Scholar.

40

Thomson, JJ. The Realm of Rights. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1992 Google Scholar; Ripstein A. Beyond the harm principle, Philosophy & Public Affairs 2006;34(3):215–45; Archard, D. Informed consent: Autonomy and self-ownership. Journal of Applied Philosophy 2008;25(1):19–34 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

41

Bublitz C, Merkel R. Crimes against minds: On mental manipulations, harms and a human right to mental self-determination. Criminal Law and Philosophy 2014;8:51–77.

42

An important conceptual question here could be whether we can conceive of a mind without a brain? As discussed in this section, reflecting common theorizing in philosophy and cognitive science accounts, many accounts of mental integrity assume embodiment (and some degree of bodily integrity). But this might imply remnant notions of mind–body dualism that would need to be addressed (which exceeds the scope of the discussion here). A member of our group has suggested to use the terminology “identity integrity” instead. For further consideration see, inter alia, Jotterand F. Personal identity, neuroprosthetics, and alzheimer’s disease. In: Jotterand, F, Ienca, M, Wangmo, T, Elger, BS, Jotterand, F, Ienca, M, et al. eds. Intelligent Assistive Technologies for Dementia: Clinical, Ethical, Social, and Regulatory Implications. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2019 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Jotterand F. Neuroethics as an anthropological project. In: Farisco M, ed. Neuroethics and Cultural Diversity (forthcoming); Jotterand, F. The Unfit Brain and the Limits of Moral Bioenhancement. Singapore: Springer; 2022 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

43

Ayer AJ. The concept of a person. In: Ayer AJ, ed. The Concept of a Person: and Other Essays. London: Macmillan Education; 1963:82–128; Rorty, R. Incorrigibility as the mark of the mental. The Journal of Philosophy 1970;67(12):399–424 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Nagel, T. What is it like to be a bat? Philosophical Review 1974;83:435–50CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Dennett DC. Consciousness Explained. London: Penguin Books; 1991.

44

Warren, S, Brandeis, L. The right to privacy. Harvard Law Review 1890;4(5):193–220 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

45

Alderman E, Kennedy C. The Right to Privacy. New York, NY: Vintage Books; 1997. Brin D. The Transparent Society: Will Technology Force us to Choose Between Privacy and Freedom? Reading, MA: Perseus Books; 1998.

46

Lynch MP. Privacy and the threat to the self, 1371942027; available at archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/22/privacy-and-the-threat-to-the-self/ (last accessed 30 Jan 2023).

47

Vansteensel, MJ, Pels, EGM, Bleichner, MG, Branco, MP, Denison, T, Freudenburg, ZV, et al. Fully implanted brain–computer interface in a locked-in patient with ALS. New England Journal of Medicine 2016;375(21):2060–66CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

48

Haselager, P, Vlek, R, Hill, J, Nijboer, F. A note on ethical aspects of BCI. Neural Networks: The Official Journal of the International Neural Network Society 2009;22(9):1352–57CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

49

Widge, AS, Dougherty, DD, Moritz, CT. Affective brain-computer interfaces as enabling technology for responsive psychiatric stimulation. Brain Computer Interfaces (Abingdon, England) 2014;1(2):126–36Google ScholarPubMed.

50

Veit, R, Singh, V, Sitaram, R, Caria, A, Rauss, K, Birbaumer, N. Using real-time fMRI to learn voluntary regulation of the anterior insula in the presence of threat-related stimuli. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 2012;7(6):623–34CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

51

Farah, MJ, Hutchinson, JB, Phelps, EA, Wagner, AD. Functional MRI-based lie detection: Scientific and societal challenges. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 2014;15(2):123–31CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed; Langleben DD, Moriarty JC. Using brain imaging for lie detection: Where science, law and research policy collide. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law : An Official Law Review of the University of Arizona College of Law and the University of Miami School of Law 2013;19(2):222–34; Shen, F. Neuroscience, mental privacy, and the law. Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy 2013;36:653–713 Google Scholar; See note 22, Farah et al. 2014.

52

Salmanowitz N. The case for pain neuroimaging in the courtroom: Lessons from deception detection. Journal of Law and the Biosciences 2015;2:139–48; Reardon S. Neuroscience in court: The painful truth. Nature 2015;518:474–6; For methodological limits of neuroimaging for legal applications see also: Kellmeyer, P. Ethical and legal implications of the methodological crisis in neuroimaging. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 2017;26:530–54CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

53

Unterrainer HF, Chen MJ-L, Gruzelier JH. EEG-neurofeedback and psychodynamic psychotherapy in a case of adolescent anhedonia with substance misuse: Mood/theta relations, International Journal of Psychophysiology: Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology 2014;93(1):84–95.

54

Bublitz J-C. My mind is mine!? Cognitive liberty as a legal concept. In: Hildt E, Franke AG, eds. Cognitive Enhancement: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer; 2013:233–64. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6253-4_19.

55

See note 54, Bublitz 2013.

56

Farahany N. The costs of changing our minds. Emory Law Journal 2019;69(1):75, at 97; See also Farahany, N. The Battle for Your Brain: Defending the Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 2023 Google Scholar.

57

See note 1, Ienca, Andorno 2017, at 11.

58

See note 36, Lavazza 2018.

59

Report commissioned by the Committee on Bioethics of COE; 2021; available at www.rm_coe.int/report; See note 13, Ienca 2021.

60

See note 56, Farahany 2023.

61

A potential precedent in addressing this worry may be found in the latest version of the Chilean Bill on neuroprotection (still being drafted), which proposes that medical as well as non-medical neurotechnologies must be registered by the National Institute of Public Health for their use in humans.

62

ECtHR 12 October 2006, appl.no. 13178/03 (Mayeka and Kaniki Mitunga/Belgium), § 83.

63

Vries K. Right to respect for private and family life. In: van Dijk P, et al. eds. Theory and Practice of the European Convention On Human Rights, 2018; ECtHR 14 January 2020, appl.no. 41288/15 (Beizaras and Levickas/Lithuania), § 128; ECtHR 7 May 2019, appl.no. 12509/13 (Panayotova and Others/Bulgaria), § 58–9.

64

See note 1, Bublitz 2020, at 388, 395.

65

See note 1, Michalowski 2020, at 406; see note 64, de Vries 2018, at 690.

66

See note 1, Bublitz 2020; see note 1, Ienca, Andorno 2017, at 18.

67

ECtHR 26 November 2009, appl.no. 25282/06 (Dolenec/Croatia), § 165; ECtHR 6 February 2001, appl.no. 44599/98 (Bensaid/UK), § 47.

68

ECtHR 24 July 2012, appl.no. 41526/10 (Đorđević/Croatia), § 97–8.

69

ECtHR 30 November 2010, appl.no. 2660/03 (Hajduová/Slovakia), § 49.

70

ECtHR 28 October 2014, appl.no. 20531/06 (Ion Cârstea/Romania) § 38; ECtHR 21 November 2013, appl. no. 16882/03 (Putistin/Ukraine), § 32; See note 1, Michalowski 2020, at 406

71

ECtHR (GC) 29 March 2016, appl.no. 56925/08 (Bédat/Switzerland), § 72; ECtHR (GC) 25 September 2018, appl.no; 76639/11 (Denisov/Ukraine), § 95

72

EU Network of Independent Experts on Fundamental Rights. Commentary of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. European Commission; 2006.

73

Nowak M. “Article 3 CFR”. In: EU Network of Independent Experts on Fundamental Rights, ed. Commentary of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. Brussels: European Commission; 2006:36.

74

Vermeulen, BP. Freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Article 9). In: van Dijk, P, van Hoof, F, van Rijn, A, Zwaak, L, eds. Theory and Practice of the European Convention on Human Rights. Antwerpen: Intersentia; 2006:751–71Google Scholar.

75

Murdoch, J. Protecting the Right to Freedom of Thought, Conscience and Religion Under the European Convention on Human Rights. Strasbourg: Council of Europe; 2012 Google Scholar.

76

General Comment No. 22: The right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Art. 18) CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4, para. 3; see note 75, Vermeulen 2006, at 751–71.

77

Harris, DJ, O’Boyle, M, Bates, E, Buckley, C. Harris. O’Boyle & Warbrick: Law of the European Convention on Human Rights. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2018 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

78

General Comment No. 22: The right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Art. 18) CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4, paras 1–2 and its preparatory work: CCPR/C/SR.1162, paras 14, 34–40; Evans, C. Freedom of Religion under the European Convention on Human Rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Partsch K. Freedom of conscience and expression, and political freedoms. In: Henkin L, ed. The International Bill of Rights: The Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1981: 213–4.

79

See note 33, Hertz 2022; UN Report FoT 2021; see note 1, McCarthy-Jones 2019; see note 1, Alegre 2017; Bublitz JC. Novel neurorights: From nonsense to substance. Neuroethics 2022;15:7.

80

Jong CD de. The Freedom of Thought, Conscience and Religion or Belief in the United Nations (1946–1992), Antwerpen: Intersentia/Hart; 2000; Evans MD, Religious Liberty and International Law in Europe. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997; see note 33, Ligthart 2022; see note 79, Partsch 1981.

81

See note 12, Ienca 2021.

82

Ligthart S, Bublitz C, Douglas T, Forsberg L, Meynen G. Rethinking the right to freedom of thought: A multidisciplinary analysis. Human Rights Law Review 2022;22:14.

83

See DARPA’s recent project on Neural Evidence Aggregation Tool (NEAT); available at www.darpa.mil/news-events/2022-03-02 (last accessed 22 Mar 2023). “NEAT aims to develop a new cognitive science tool that identifies people at risk of suicide by using preconscious brain signals rather than asking questions and waiting for consciously filtered responses.” See also: Haselager, P, Mecacci, G, Wolkenstein, A. Clinical neurotechnology meets artificial intelligence. In: Friedrich, O, Wolkenstein, A, Bublitz, C, Jox, RJ, Racine, E, eds. Philosophical, Ethical, Legal and Social Implications. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021.55–68Google Scholar. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-64590-8_5.

84

Chandler, JA, Van der Loos, KI, Boehnke, SE, Beaudry, JS, Buchman, DZ, Illes, J. Building communication neurotechnology for high stakes communications. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2021;22(10):587–88CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed; Maslen, H, Rainey, S. “A steadying hand”: Ascribing speech acts to users of predictive speech assistive technologies. Journal of Law and Medicine 2018;26(1):44–53 Google ScholarPubMed.

85

UN Human Rights Council, The right to privacy in the digital age, A/HRC/39/29, 3 August 2018, para. 5.

86

CCPR General Comment No. 16: Article 17 (Right to Privacy), para. 1.

87

UN Human Rights Council, The right to privacy in the digital age, A/HRC/39/29, 3 August 2018, para. 5.

88

UN Human Rights Council, The right to privacy in the digital age, A/HRC/39/29, 3 August 2018, para. 5.

89

UN Human Rights Council, The right to privacy in the digital age, A/HRC/39/29, 3 August 2018, para. 15.

90

ECtHR (GC) 5 September 2017, appl.no. 61496/08 (Bărbulescu/Romania), § 70.

91

ECtHR (GC) 27 June 2017, appl.no. 931/13 (Satakunnan Markkinapörssi Oy and Satamedia Oy/Finland), § 137 (emphasis added).

92

ECtHR (GC) 4 December 2008, appl.nos. 30562/04 and 30566/04 (S. & Marper/UK), § 67; ECtHR 13 February 2020, appl.no. 45245/15 (Gaughran/UK), § 70. See note 64, de Vries 2018, at 673.

93

Council of Europe. The European Convention on Human Rights: A Living Instrument. Strasbourg 2020:7.

94

Article 4(1) GDPR.

95

See note 4, Rainey et al. 2020; see note 1, Ienca, Andorno 2017.

96

See note 29, Bublitz 2014; see note 1, Ligthart et al. 2021.

97

General Comment No. 22: The right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Art. 18) CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4, para. 3; see note 64, Vermeulen 2006.

98

Shaheed, UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, Report on the Freedom of Thought, 5 October 2021, A/76/380, at 94, para. 26.

99

See note 33, Bublitz 2014; see note 1, Alegre 2017; see note 1, McCarthy-Jones 2019; see note 1, Ligthart 2020.

100

See 82, Ligthart et al. 2022.

101

Rainey, B, Wicks, E, Jacobs, Ovey C., White and Ovey: The European Convention on Human Rights. 8th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2020 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; see note 77, Harris 2018.

102

General comment No. 34 Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression, CCPR/C/GC/34, paras 11–12; ECtHR (GC) 15 December 2005, appl.no 73797/01 (Kyprianou/Cyprus), § 174; Interamerican Commission on Human Rights, Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression, principle 2; Grossman, C. Freedom of expression in the inter-american system for the protection of human rights. ILSA Journal of International & Comparative Law 2001;7(3):619–47Google Scholar.

103

General comment No. 34 Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression, CCPR/C/GC/34, para. 10.

104

See note 77, Harris 2018, at 595. See, for example, EComHR 7 April 1994, appl.no. 20871/92 (Strohal/Austria); ECtHR (GC) 3 April 2012, appl.no. 41723/06 (Gillberg/Sweden), § 86; ECtHR 23 October 2018, appl.no. 26892/12 (Wanner/Germany), § 39–42. An important note: This suggests that the right to silence has been protected by the ECtHR. The response of the ECtHR to English attacks on the right to silence suggests otherwise. One can remain silent, but adverse inferences can be drawn from the person’s silence, which does not amount to much of a protection of the right to silence. In the future we might expect the ECtHR to extend its approach by saying a person can refuse brain-based lie detection that the state wants to employ, but if the person does so, adverse inferences can be drawn from the refusal.

105

See note 33, Ligthart 2022; see note 1, Ligthart 2020.

106

See note 33, Ligthart 2022.

107

Sententia, W. Neuroethical considerations: Cognitive liberty and converging technologies for improving human cognition. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2004; 1013:221–28CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Bublitz, C, Cognitive liberty or the international human right to freedom of thought. In: Clausen, J, Levy, N, eds. Handbook of Neuroethics. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer; 2015:1309–33CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

108

See note 56, Farahany 2019, 2023.

109

See note 1, Bublitz 2020; see note 1, Ienca, Andorno 2017; see note 41, Bublitz, Merkel 2014.

110

Ligthart, S, Kooijmans, T, Douglas, T, Meynen, G. Closed-loop brain devices in offender rehabilitation: Autonomy, human rights, and accountability. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 2021;30(4):669–80CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed; Kellmeyer, P, Cochrane, T, Müller, O, Mitchell, C, Ball, T, Fins, JJ, et al. The effects of closed-loop medical devices on the autonomy and accountability of persons and systems. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 2016;25:623–33CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

111

See note 4, Committee on Bioethics of the Council of Europe 2019; § 21–22 (emphasis added).

112

See note 1, Bublitz 2020, at 397.

113

ECtHR 12 October 2006, appl.no. 13178/03 (Mayeka and Kaniki Mitunga/Belgium), § 83.

114

ECtHR (GC) 27 August 2015, appl.no. 46470/11 (Parrillo/Italy), § 153.

115

ECtHR (GC) 27 June 2017, appl.no. 931/13 (Satakunnan Markkinapörssi Oy and Satamedia Oy/Finland), § 137.

116

Either as an individual notion or as part of the right to mental integrity.

117

Ligthart, S, Meynen, G, Biller-Andorno, N, Kooijmans, T, Kellmeyer, P. Is virtually everything possible? The relevance of ethics and human rights for introducing extended reality in forensic psychiatry. AJOB Neuroscience 2022;13(3):144–57CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed.

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic  “That the manufacture of consent is capable of great refinements no one, I think, denies. The process by which

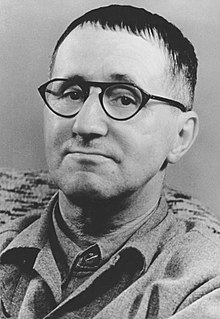

“That the manufacture of consent is capable of great refinements no one, I think, denies. The process by which  A Tui is an intellectual who sells his or her abilities and opinions as a commodity in the marketplace or who uses them to support the dominant ideology of an oppressive society. The German modernist theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht invented the term and used it in a range of critical and creative projects, including the material that he developed in the mid-1930s for his so-called Tui-Novel—an unfinished satire on intellectuals in the German Empire and Weimar Republic—and his epic comedy from the early 1950s, Turandot or the Whitewashers’ Congress. The word is a neologism that results from the acronym of a word play on “intellectual” (“Tellekt-Ual-In”).

A Tui is an intellectual who sells his or her abilities and opinions as a commodity in the marketplace or who uses them to support the dominant ideology of an oppressive society. The German modernist theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht invented the term and used it in a range of critical and creative projects, including the material that he developed in the mid-1930s for his so-called Tui-Novel—an unfinished satire on intellectuals in the German Empire and Weimar Republic—and his epic comedy from the early 1950s, Turandot or the Whitewashers’ Congress. The word is a neologism that results from the acronym of a word play on “intellectual” (“Tellekt-Ual-In”). “It is very useful to differentiate between

“It is very useful to differentiate between