| Name |

Description |

| Ambiguity effect |

The tendency to avoid options for which missing information makes the probability seem “unknown”.[10] |

| Anchoring or focalism |

The tendency to rely too heavily, or “anchor”, on one trait or piece of information when making decisions (usually the first piece of information acquired on that subject).[11][12] |

| Anthropocentric thinking |

The tendency to use human analogies as a basis for reasoning about other, less familiar, biological phenomena.[13] |

| Anthropomorphism or personification |

The tendency to characterize animals, objects, and abstract concepts as possessing human-like traits, emotions, and intentions.[14] |

| Attentional bias |

The tendency of perception to be affected by recurring thoughts.[15] |

| Automation bias |

The tendency to depend excessively on automated systems which can lead to erroneous automated information overriding correct decisions.[16] |

| Availability heuristic |

The tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events with greater “availability” in memory, which can be influenced by how recent the memories are or how unusual or emotionally charged they may be.[17] |

| Availability cascade |

A self-reinforcing process in which a collective belief gains more and more plausibility through its increasing repetition in public discourse (or “repeat something long enough and it will become true”).[18] |

| Backfire effect |

The reaction to disconfirming evidence by strengthening one’s previous beliefs.[19] cf. Continued influence effect. |

| Bandwagon effect |

The tendency to do (or believe) things because many other people do (or believe) the same. Related to groupthink and herd behavior.[20] |

| Base rate fallacy or Base rate neglect |

The tendency to ignore base rate information (generic, general information) and focus on specific information (information only pertaining to a certain case).[21] |

| Belief bias |

An effect where someone’s evaluation of the logical strength of an argument is biased by the believability of the conclusion.[22] |

| Ben Franklin effect |

A person who has performed a favor for someone is more likely to do another favor for that person than they would be if they had received a favor from that person.[23] |

| Berkson’s paradox |

The tendency to misinterpret statistical experiments involving conditional probabilities.[24] |

| Bias blind spot |

The tendency to see oneself as less biased than other people, or to be able to identify more cognitive biases in others than in oneself.[25] |

| Bystander effect |

The tendency to think that others will act in an emergency situation.[26] |

| Choice-supportive bias |

The tendency to remember one’s choices as better than they actually were.[27] |

| Clustering illusion |

The tendency to overestimate the importance of small runs, streaks, or clusters in large samples of random data (that is, seeing phantom patterns).[12] |

| Confirmation bias |

The tendency to search for, interpret, focus on and remember information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions.[28] |

| Congruence bias |

The tendency to test hypotheses exclusively through direct testing, instead of testing possible alternative hypotheses.[12] |

| Conjunction fallacy |

The tendency to assume that specific conditions are more probable than general ones.[29] |

| Conservatism (belief revision) |

The tendency to revise one’s belief insufficiently when presented with new evidence.[5][30][31] |

| Continued influence effect |

The tendency to believe previously learned misinformation even after it has been corrected. Misinformation can still influence inferences one generates after a correction has occurred.[32] cf. Backfire effect |

| Contrast effect |

The enhancement or reduction of a certain stimulus’ perception when compared with a recently observed, contrasting object.[33] |

| Courtesy bias |

The tendency to give an opinion that is more socially correct than one’s true opinion, so as to avoid offending anyone.[34] |

| Curse of knowledge |

When better-informed people find it extremely difficult to think about problems from the perspective of lesser-informed people.[35] |

| Declinism |

The predisposition to view the past favorably (rosy retrospection) and future negatively.[36] |

| Decoy effect |

Preferences for either option A or B change in favor of option B when option C is presented, which is completely dominated by option B (inferior in all respects) and partially dominated by option A.[37] |

| Default effect |

When given a choice between several options, the tendency to favor the default one.[38] |

| Denomination effect |

The tendency to spend more money when it is denominated in small amounts (e.g., coins) rather than large amounts (e.g., bills).[39] |

| Disposition effect |

The tendency to sell an asset that has accumulated in value and resist selling an asset that has declined in value.[40] |

| Distinction bias |

The tendency to view two options as more dissimilar when evaluating them simultaneously than when evaluating them separately.[41] |

| Dunning–Kruger effect |

The tendency for unskilled individuals to overestimate their own ability and the tendency for experts to underestimate their own ability.[42] |

| Duration neglect |

The neglect of the duration of an episode in determining its value.[43] |

| Empathy gap |

The tendency to underestimate the influence or strength of feelings, in either oneself or others.[44] |

| Endowment effect |

The tendency for people to demand much more to give up an object than they would be willing to pay to acquire it.[45] |

| Exaggerated expectation |

Based on the estimates,[clarification needed] real-world evidence turns out to be less extreme than our expectations (conditionally inverse of the conservatism bias).[unreliable source?][5][46] |

| Experimenter’s or expectation bias |

The tendency for experimenters to believe, certify, and publish data that agree with their expectations for the outcome of an experiment, and to disbelieve, discard, or downgrade the corresponding weightings for data that appear to conflict with those expectations.[47] |

| Focusing effect |

The tendency to place too much importance on one aspect of an event.[48] |

| Forer effect or Barnum effect |

The observation that individuals will give high accuracy ratings to descriptions of their personality that supposedly are tailored specifically for them, but are in fact vague and general enough to apply to a wide range of people. This effect can provide a partial explanation for the widespread acceptance of some beliefs and practices, such as astrology, fortune telling, graphology, and some types of personality tests.[49] |

| Form function attribution bias |

In human–robot interaction, the tendency of people to make systematic errors when interacting with a robot. People may base their expectations and perceptions of a robot on its appearance (form) and attribute functions which do not necessarily mirror the true functions of the robot.[50] |

| Framing effect |

Drawing different conclusions from the same information, depending on how that information is presented.[51] |

| Frequency illusion |

The illusion in which a word, a name, or other thing that has recently come to one’s attention suddenly seems to appear with improbable frequency shortly afterwards (not to be confused with the recency illusion or selection bias).[52] This illusion is sometimes referred to as the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon.[53] |

| Functional fixedness |

Limits a person to using an object only in the way it is traditionally used.[54] |

| Gambler’s fallacy |

The tendency to think that future probabilities are altered by past events, when in reality they are unchanged. The fallacy arises from an erroneous conceptualization of the law of large numbers. For example, “I’ve flipped heads with this coin five times consecutively, so the chance of tails coming out on the sixth flip is much greater than heads.”[55] |

| Hard–easy effect |

Based on a specific level of task difficulty, the confidence in judgments is too conservative and not extreme enough.[5][56][57][58] |

| Hindsight bias |

Sometimes called the “I-knew-it-all-along” effect, the tendency to see past events as being predictable[59] at the time those events happened. |

| Hostile attribution bias |

The “hostile attribution bias” is the tendency to interpret others’ behaviors as having hostile intent, even when the behavior is ambiguous or benign.[60] |

| Hot-hand fallacy |

The “hot-hand fallacy” (also known as the “hot hand phenomenon” or “hot hand”) is the belief that a person who has experienced success with a random event has a greater chance of further success in additional attempts. |

| Hyperbolic discounting |

Discounting is the tendency for people to have a stronger preference for more immediate payoffs relative to later payoffs. Hyperbolic discounting leads to choices that are inconsistent over time – people make choices today that their future selves would prefer not to have made, despite using the same reasoning.[61] Also known as current moment bias, present-bias, and related to Dynamic inconsistency. A good example of this: a study showed that when making food choices for the coming week, 74% of participants chose fruit, whereas when the food choice was for the current day, 70% chose chocolate. |

| Identifiable victim effect |

The tendency to respond more strongly to a single identified person at risk than to a large group of people at risk.[62] |

| IKEA effect |

The tendency for people to place a disproportionately high value on objects that they partially assembled themselves, such as furniture from IKEA, regardless of the quality of the end result.[63] |

| Illicit transference |

Occurs when a term in the distributive (referring to every member of a class) and collective (referring to the class itself as a whole) sense are treated as equivalent. The two variants of this fallacy are the fallacy of composition and the fallacy of division. |

| Illusion of control |

The tendency to overestimate one’s degree of influence over other external events.[64] |

| Illusion of validity |

Belief that our judgments are accurate, especially when available information is consistent or inter-correlated.[65] |

| Illusory correlation |

Inaccurately perceiving a relationship between two unrelated events.[66][67] |

| Illusory truth effect |

A tendency to believe that a statement is true if it is easier to process, or if it has been stated multiple times, regardless of its actual veracity. These are specific cases of truthiness. |

| Impact bias |

The tendency to overestimate the length or the intensity of the impact of future feeling states.[68] |

| Information bias |

The tendency to seek information even when it cannot affect action.[69] |

| Insensitivity to sample size |

The tendency to under-expect variation in small samples. |

| Irrational escalation |

The phenomenon where people justify increased investment in a decision, based on the cumulative prior investment, despite new evidence suggesting that the decision was probably wrong. Also known as the sunk cost fallacy. |

| Law of the instrument |

An over-reliance on a familiar tool or methods, ignoring or under-valuing alternative approaches. “If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” |

| Less-is-better effect |

The tendency to prefer a smaller set to a larger set judged separately, but not jointly. |

| Look-elsewhere effect |

An apparently statistically significant observation may have actually arisen by chance because of the size of the parameter space to be searched. |

| Loss aversion |

The disutility of giving up an object is greater than the utility associated with acquiring it.[70] (see also Sunk cost effects and endowment effect). |

| Mere exposure effect |

The tendency to express undue liking for things merely because of familiarity with them.[71] |

| Money illusion |

The tendency to concentrate on the nominal value (face value) of money rather than its value in terms of purchasing power.[72] |

| Moral credential effect |

The tendency of a track record of non-prejudice to increase subsequent prejudice. |

| Negativity bias or Negativity effect |

Psychological phenomenon by which humans have a greater recall of unpleasant memories compared with positive memories.[73][74] (see also actor-observer bias, group attribution error, positivity effect, and negativity effect).[75] |

| Neglect of probability |

The tendency to completely disregard probability when making a decision under uncertainty.[76] |

| Normalcy bias |

The refusal to plan for, or react to, a disaster which has never happened before. |

| Not invented here |

Aversion to contact with or use of products, research, standards, or knowledge developed outside a group. Related to IKEA effect. |

| Observer-expectancy effect |

When a researcher expects a given result and therefore unconsciously manipulates an experiment or misinterprets data in order to find it (see also subject-expectancy effect). |

| Omission bias |

The tendency to judge harmful actions (commissions) as worse, or less moral, than equally harmful inactions (omissions).[77] |

| Optimism bias |

The tendency to be over-optimistic, overestimating favorable and pleasing outcomes (see also wishful thinking, valence effect, positive outcome bias).[78][79] |

| Ostrich effect |

Ignoring an obvious (negative) situation. |

| Outcome bias |

The tendency to judge a decision by its eventual outcome instead of based on the quality of the decision at the time it was made. |

| Overconfidence effect |

Excessive confidence in one’s own answers to questions. For example, for certain types of questions, answers that people rate as “99% certain” turn out to be wrong 40% of the time.[5][80][81][82] |

| Pareidolia |

A vague and random stimulus (often an image or sound) is perceived as significant, e.g., seeing images of animals or faces in clouds, the man in the moon, and hearing non-existent hidden messages on records played in reverse. |

| Pessimism bias |

The tendency for some people, especially those suffering from depression, to overestimate the likelihood of negative things happening to them. |

| Placebo effect |

The belief that a medication works—even if merely a placebo. |

| Planning fallacy |

The tendency to underestimate task-completion times.[68] |

| Post-purchase rationalization |

The tendency to persuade oneself through rational argument that a purchase was good value. |

| Pro-innovation bias |

The tendency to have an excessive optimism towards an invention or innovation’s usefulness throughout society, while often failing to identify its limitations and weaknesses. |

| Projection bias |

The tendency to overestimate how much our future selves share one’s current preferences, thoughts and values, thus leading to sub-optimal choices.[83][84][74] |

| Pseudocertainty effect |

The tendency to make risk-averse choices if the expected outcome is positive, but make risk-seeking choices to avoid negative outcomes.[85] |

| Reactance |

The urge to do the opposite of what someone wants you to do out of a need to resist a perceived attempt to constrain your freedom of choice (see also Reverse psychology). |

| Reactive devaluation |

Devaluing proposals only because they purportedly originated with an adversary. |

| Recency illusion |

The illusion that a phenomenon one has noticed only recently is itself recent. Often used to refer to linguistic phenomena; the illusion that a word or language usage that one has noticed only recently is an innovation when it is in fact long-established (see also frequency illusion). |

| Regressive bias |

A certain state of mind wherein high values and high likelihoods are overestimated while low values and low likelihoods are underestimated.[5][86][87][unreliable source?] |

| Restraint bias |

The tendency to overestimate one’s ability to show restraint in the face of temptation. |

| Rhyme as reason effect |

Rhyming statements are perceived as more truthful. A famous example being used in the O.J Simpson trial with the defense’s use of the phrase “If the gloves don’t fit, then you must acquit.” |

| Risk compensation / Peltzman effect |

The tendency to take greater risks when perceived safety increases. |

| Selection bias |

The tendency to notice something more when something causes us to be more aware of it, such as when we buy a car, we tend to notice similar cars more often than we did before. They are not suddenly more common – we just are noticing them more. Also called the Observational Selection Bias. |

| Selective perception |

The tendency for expectations to affect perception. |

| Semmelweis reflex |

The tendency to reject new evidence that contradicts a paradigm.[31] |

| Sexual overperception bias / sexual underperception bias |

The tendency to over-/underestimate sexual interest of another person in oneself. |

| Social comparison bias |

The tendency, when making decisions, to favour potential candidates who don’t compete with one’s own particular strengths.[88] |

| Social desirability bias |

The tendency to over-report socially desirable characteristics or behaviours in oneself and under-report socially undesirable characteristics or behaviours.[89] |

| Status quo bias |

The tendency to like things to stay relatively the same (see also loss aversion, endowment effect, and system justification).[90][91] |

| Stereotyping |

Expecting a member of a group to have certain characteristics without having actual information about that individual. |

| Subadditivity effect |

The tendency to judge probability of the whole to be less than the probabilities of the parts.[92] |

| Subjective validation |

Perception that something is true if a subject’s belief demands it to be true. Also assigns perceived connections between coincidences. |

| Surrogation |

Losing sight of the strategic construct that a measure is intended to represent, and subsequently acting as though the measure is the construct of interest. |

| Survivorship bias |

Concentrating on the people or things that “survived” some process and inadvertently overlooking those that didn’t because of their lack of visibility. |

| Time-saving bias |

Underestimations of the time that could be saved (or lost) when increasing (or decreasing) from a relatively low speed and overestimations of the time that could be saved (or lost) when increasing (or decreasing) from a relatively high speed. |

| Third-person effect |

Belief that mass communicated media messages have a greater effect on others than on themselves. |

| Parkinson’s law of triviality |

The tendency to give disproportionate weight to trivial issues. Also known as bikeshedding, this bias explains why an organization may avoid specialized or complex subjects, such as the design of a nuclear reactor, and instead focus on something easy to grasp or rewarding to the average participant, such as the design of an adjacent bike shed.[93] |

| Unit bias |

The standard suggested amount of consumption (e.g., food serving size) is perceived to be appropriate, and a person would consume it all even if it is too much for this particular person.[94] |

| Weber–Fechner law |

Difficulty in comparing small differences in large quantities. |

| Well travelled road effect |

Underestimation of the duration taken to traverse oft-traveled routes and overestimation of the duration taken to traverse less familiar routes. |

| Women are wonderful effect |

A tendency to associate more positive attributes with women than with men. |

| Zero-risk bias |

Preference for reducing a small risk to zero over a greater reduction in a larger risk. |

| Zero-sum bias |

A bias whereby a situation is incorrectly perceived to be like a zero-sum game (i.e., one person gains at the expense of another). |

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic  “That the manufacture of consent is capable of great refinements no one, I think, denies. The process by which

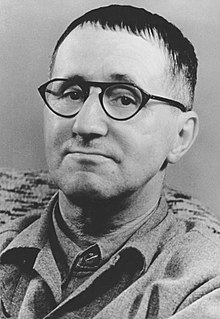

“That the manufacture of consent is capable of great refinements no one, I think, denies. The process by which  A Tui is an intellectual who sells his or her abilities and opinions as a commodity in the marketplace or who uses them to support the dominant ideology of an oppressive society. The German modernist theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht invented the term and used it in a range of critical and creative projects, including the material that he developed in the mid-1930s for his so-called Tui-Novel—an unfinished satire on intellectuals in the German Empire and Weimar Republic—and his epic comedy from the early 1950s, Turandot or the Whitewashers’ Congress. The word is a neologism that results from the acronym of a word play on “intellectual” (“Tellekt-Ual-In”).

A Tui is an intellectual who sells his or her abilities and opinions as a commodity in the marketplace or who uses them to support the dominant ideology of an oppressive society. The German modernist theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht invented the term and used it in a range of critical and creative projects, including the material that he developed in the mid-1930s for his so-called Tui-Novel—an unfinished satire on intellectuals in the German Empire and Weimar Republic—and his epic comedy from the early 1950s, Turandot or the Whitewashers’ Congress. The word is a neologism that results from the acronym of a word play on “intellectual” (“Tellekt-Ual-In”). “It is very useful to differentiate between

“It is very useful to differentiate between