Show/hide publication abstract

Show/hide publication abstract

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.07.019

DOI URL

directSciHub download

"Disobedience is the true foundation of liberty. The obedient must be slaves." ~Henry David Thoreau

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.07.019

DOI URL

directSciHub download

The individual comes face-to-face with a conspiracy so monstrous he cannot believe it exists. The American mind has not come to a realisation of the evil which has been introduced into our midst. It rejects even the assumption that human creatures could espouse a philosophy which must ultimately destroy all that is good and decent.

When morals decline and good men do nothing, evil flourishes. A society unwilling to learn from past is doomed. We must never forget our history.

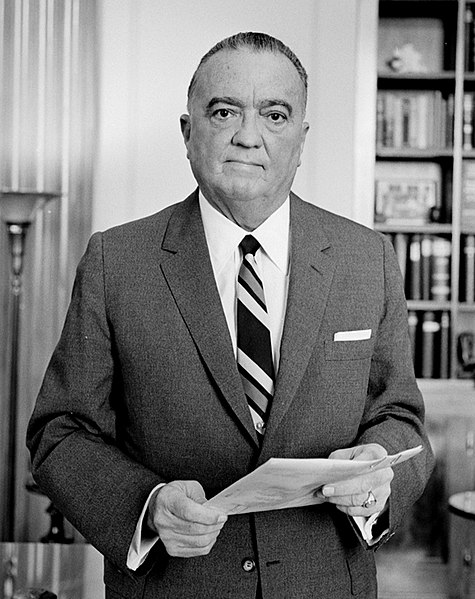

John Edgar Hoover was an American law enforcement administrator and the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the United States. He was appointed as the director of the Bureau of Investigation – the FBI’s predecessor – in 1924 and was instrumental in founding the FBI in 1935, where he remained director until his death in 1972 at the age of 77

“Violations of moral norms can be made ‘morally invisible’ even if all relevant facts are unobscured: This can be achieved by embedding these facts into a context that prevents eliciting widespread unease and indignation. One example is the structural violence associated with the implementation of neoliberal economical doctrine. While societal and humanitarian consequences of this violence have so far been mostly observed in so-called third-world countries, they also manifest themselves more and more often in western industrialized nations. Mass media play a pivotal role in making facts morally and cognitively visible: In addition to reporting simple facts, media typically also deliver the contextual frame necessary for interpreting the facts, thus shaping our political world view. The invisibility of some moral transgressions is thus part of our daily live and concerns us all.” (Mausfeld, 2015)

See also: uni-kiel.de/psychologie/mausfeld

If information is partially occluded and fragmented, we are oftentimes unable to identify the underlying pattern (see Figure 1).

However, as soon as the causal reason for the fragmentation becomes available to us (i.e., when we become aware of the visual or ideological “mask”) we are able to use inferential deductive cognitive reasoning processes to identify (and understand) the underlying pattern – despite the fragmentation of information/knowledge (see Figure 2). Without this “causative information” which masks the underlying pattern the likelihood of successful pattern recognition is minute (note that both figures display the letter “R” in various orientations – the difference between them is that Figure 2 shows the mask whereas Figure 1 does not) .Insight1 (cf. Köhler, 1925)2 into the mechanism which causes the occlusion and fragmentation thus allows us to understand the broader meaning of the percept (or the psychological narrative), viz., we are able to see “the bigger picture” in context. This contextual knowledge can be a visual mask or a historical pattern (as outlined below). The adumbrated perceptual analogy is thus generalisable across prima vista unrelated domains (i.e., it is domain non-specific).The same idea can be applied to the social sphere. An understanding of the mechanisms which undergird “neoliberal psychological indoctrination” is crucial in order to understand the “bigger picture” – the “holistic gestalt” (Ash, 1998; Sharps & Wertheimer, 2000) of the social, political, economic, and academic environment we inhabit. Based on this overarching knowledge we can then “try our best” to take an appropriate and responsible course of action. However, we first have to perceive and acknowledge the problem. That is, a valid diagnosis is primary. Without this broader understanding we “lose sight of the wood for the trees” (cf. global vs. local perception/information processing), that is, we attend to seemingly unrelated semantic information fragments without an understanding of their mutual interrelations. Interestingly, emotions & affective states play a significant modulatory role in the underlying cognitive processes (e.g., Basso, Schefft, Ris, & Dember, 1996; Gasper & Clore, 2002; Huntsinger, Clore, & Bar-Anan, 2010). In other words, our emotional system is centrally involved in perception and reasoning. Therefore, the emotional system (i.e., limbic system) can be systematically manipulated in order to interfere with rational higher-order (prefrontal) cognitive processes which are necessary for logical inferential reasoning and problem-solving. Primordial fear (phylogenetically ancient amygdalae circuitry) is perhaps the most significant inhibitor of higher-order cognitive processes.

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1038/nrn3301

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1111/1467-8721.00181

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1017/sjp.2014.70

DOI URL

directSciHub download

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.” (Edward Bernays, Propaganda, 1928)

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.” (Edward Bernays, Propaganda, 1928)

According to Clark (2006):

“… the critique of intellectuals which Brecht developed… around the notion of ‘Tuismus’ engages a model of the public intellectual in which the self-image of the artist and thinker as a socially and politically engaged person corresponded to the expectations of the public.”

But there is another kind of authority, rational authority by which I mean any authority which is based on competence and knowledge, which permits criticism, which by its very nature tends to diminish, but which is not based on the emotional factors of submission and masochism, but on the realistic recognition of the competence of the person for a certain job.”

― 1958. The Moral Responsibility of Modern Man, in: Merrill-Palmer. Quarterly of Behavior and Development, Detroit, Vol. 5, p. 6.

“No expert certification is required to think about these questions, even if the ruling elites try their best to restrict discourse about them to a narrow group of “qualified experts”. As “citoyens”, well-informed and dutiful citizens trying to actively participate in forming our community, we possess what in the age of enlightenment came to be called “lumen naturale”: We are endowed with a natural reasoning faculty that allows us to engage in debates and decisions about matters which directly affect us. We can therefore adequately discuss the essential core of the ways in which grave violations of law and morality are hidden from our awareness without having some specialist education.” (Mausfeld, 2015)

By contrast, compare the following websites for more information on the actual origin of the “conspiracy theory meme”. According to the in-depth analyses of these scholars, governmental ‘think tanks’ (e.g., well-paid social psychologists) played a crucial role in the invention of the term “conspiracy theory” which is used to prima facie discredit those who challenge the mainstream narrative propagandized by the mass-media and other other social institutions (e.g., schools & universities). The social sciences & humanities have a long well-documented history of contributing to the systematic manipulation of public attitudes & opinions (the public relations industry and the social sciences/humanities are obviously deeply intertwined) (cf. weaponized anthropology). Today, the cognitive neurosciences joined the choir (cf. techniques of neuro-marketing). Psychology (and science in general) is a two-sided sword. It can be used to contribute to the unfoldment of human potential (the humanistic perspective which emphasises liberty and self-actualisation a la Maslow) or the same methods can be used to manipulate and control people (the neoliberal doctrine a la Bernays which focuses on power and submission to authority). It is self-evident on which side of the bipolar continuum (viz., humanism versus neoliberalism) humanity finds itself at the moment…

Connecting the dots: Illusory pattern perception predicts belief in conspiracies and the supernatural

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5900972/pdf/EJSP-48-320.pdf

See also: conspiracytheories.eu/activity/canterbury-training-school/

Ash, M. G. (1998). Gestalt psychology in German culture, 1890-1967 : holism and the quest for objectivity. Cambridge Studies in the History of Psychology. doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.6b02599

Basso, M. R., Schefft, B. K., Ris, M. D., & Dember, W. N. (1996). Mood and global-local visual processing. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. doi.org/10.1017/S1355617700001193

Gasper, K., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Attending to the big picture: Mood and global versus local processing of visual information. Psychological Science. doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00406

Huntsinger, J. R., Clore, G. L., & Bar-Anan, Y. (2010). Mood and Global-Local Focus: Priming a Local Focus Reverses the Link Between Mood and Global-Local Processing. Emotion. doi.org/10.1037/a0019356

Sharps, M. J., & Wertheimer, M. (2000). Gestalt Perspectives on Cognitive Science and on Experimental Psychology. Review of General Psychology. doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.4.4.315

The five techniques (also know as Deep-Interrogation) were illegal interrogation methods which were originally developed by the British military in other operational theatres and then applied to detainees during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. They have been defined as prolonged wall-standing, hooding, subjection to noise, deprivation of sleep, and deprivation of food and drink.[1]

They were first used in Northern Ireland in 1971 as part of Operation Demetrius – the mass arrest and internment (imprisonment without trial) of people suspected of involvement with the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Out of those arrested, fourteen were subjected to a programme of “deep interrogation” using the five techniques. This took place at a secret interrogation centre in Northern Ireland. For seven days, when not being interrogated, the detainees were kept hooded and handcuffed in a cold cell and subjected to a continuous loud hissing noise. Here they were forced to stand in a stress position for many hours and were deprived of sleep, food and drink. They were also repeatedly beaten, and some reported being kicked in the genitals, having their heads banged against walls and being threatened with injections. The effect was prolonged pain, physical and mental exhaustion, severe anxiety, depression, hallucinations, disorientation and repeated loss of consciousness.[2][3] It also resulted in long-term psychological trauma. The fourteen became known as “the Hooded Men” and were the only detainees in Northern Ireland subjected to all five techniques together. Other detainees were subjected to at least one of the five techniques along with other interrogation methods.[4]

In 1976, the European Commission of Human Rights ruled that the five techniques amounted to torture. The case was then referred to the European Court of Human Rights. In 1978 the court ruled that the techniques were “inhuman and degrading” and breached the European Convention on Human Rights, but did not amount to “torture”. In 2014, after new information was uncovered that showed the decision to use methods of torture in Northern Ireland in 1971-1972 had been taken by ministers,[5] the Irish Government asked the European Court of Human Rights to review its judgement and acknowledge the five techniques as torture.

The Court’s ruling that the five techniques did not amount to torture was later cited by the United States and Israel to justify their own interrogation methods,[6] which included the five techniques.[7] British agents also taught the five techniques to the forces of Brazil’s military dictatorship.[8]

During the Iraq War, the illegal use of the five techniques by British soldiers contributed to the death of Baha Mousa.[9][10]

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1017/S002081830808003X

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00441.x

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1002/9780470692486

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1177/2156587216641830

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1080/00210862.2011.594634

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1109/ICDAR.2003.1227788

DOI URL

directSciHub download