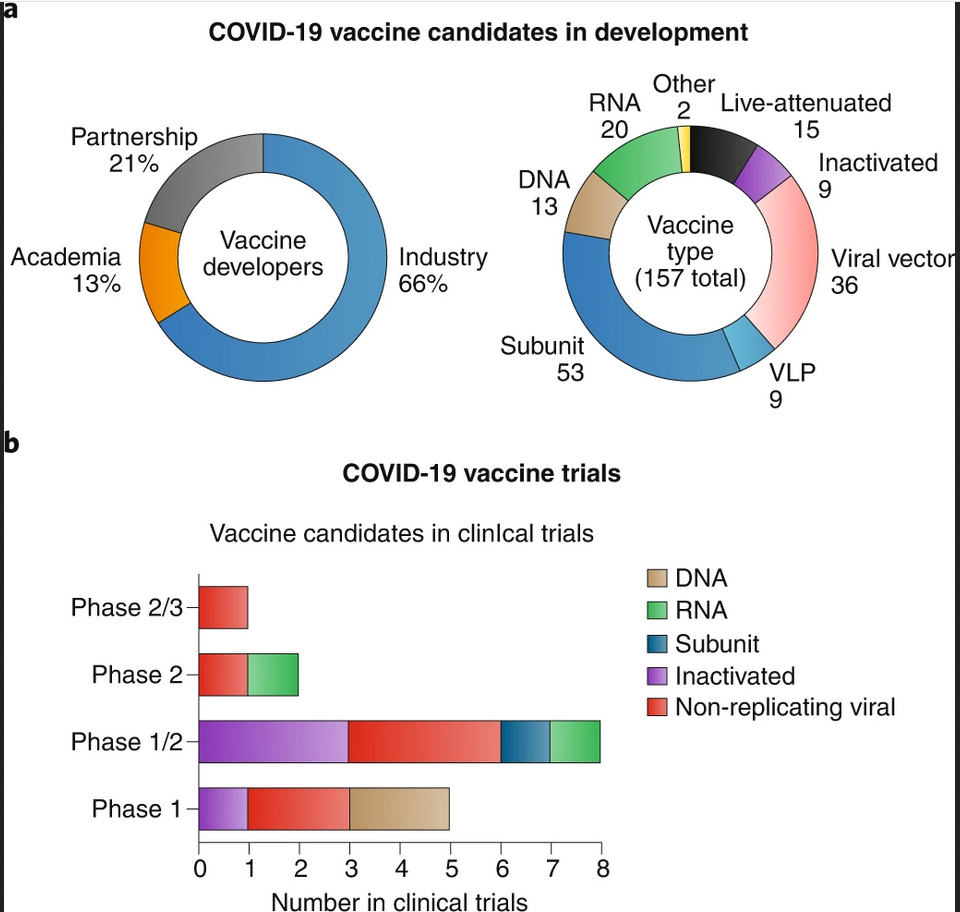

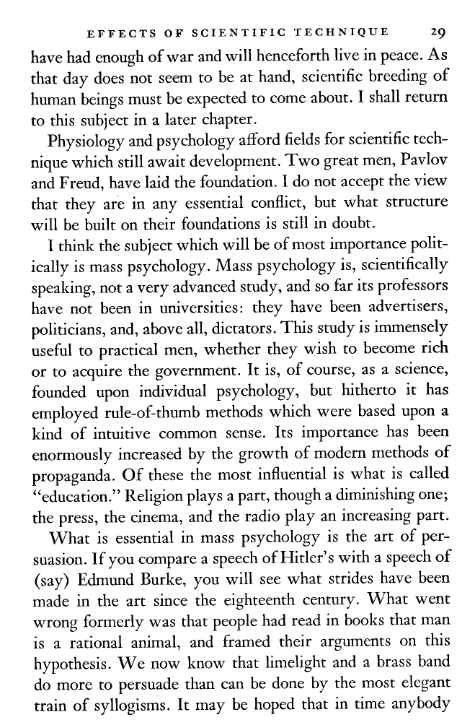

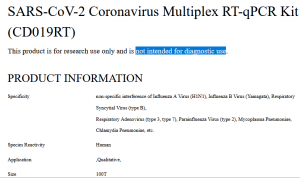

Belief perseverance (also known as conceptual conservatism[1]) is maintaining a belief despite new information that firmly contradicts it.[2] Such beliefs may even be strengthened when others attempt to present evidence debunking them, a phenomenon known as the backfire effect (compare boomerang effect).[3] For example, an article in a 2014 article in The Atlantic, journalist Cari Romm describes a study involving vaccination hesitancy. In the study, the subjects were concerned of the side effects of flu shots, and became less willing to receive them after being told that the vaccination was entirely safe.[4]

There are three kinds of backfire effects: Familiarity Backfire Effect (from making myths more familiar), Overkill Backfire Effect (from providing too many arguments), and Worldview Backfire Effect (from providing evidence that threatens someone’s worldview). According to Cook & Lewandowsky (2011), there are a number of techniques to debunk misinformation. They suggest emphasizing the core facts and not the myth. If you must mention the myth, before you do, provide an explicit warning that the upcoming information is false. Finally, provide an alternative explanation to fill the gaps left by debunking the misinformation.[5]

Since rationality involves conceptual flexibility,[6][7] belief perseverance is consistent with the view that human beings act at times in an irrational manner. Philosopher F.C.S. Schiller holds that belief perseverance “deserves to rank among the fundamental ‘laws’ of nature”.[8]

Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belief_perseverance

Further References

Wood, T., & Porter, E. (2019). The Elusive Backfire Effect: Mass Attitudes’ Steadfast Factual Adherence. Political Behavior. doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9443-y

Petrova, P. K., & Cialdini, R. E. (2005). Fluency of consumption imagery and the backfire effects of imagery appeals. Journal of Consumer Research. doi.org/10.1086/497556

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior. doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

Peter, C., & Koch, T. (2016). When Debunking Scientific Myths Fails (and When It Does Not): The Backfire Effect in the Context of Journalistic Coverage and Immediate Judgments as Prevention Strategy. Science Communication. doi.org/10.1177/1075547015613523

Brown, C. L., & Krishna, A. (2004). The skeptical shopper: A metacognitive account for the effects of default options on choice. Journal of Consumer Research. doi.org/10.1086/425087

Claus, B., Geyskens, K., Millet, K., & Dewitte, S. (2012). The referral backfire effect: The identity-threatening nature of referral failure. International Journal of Research in Marketing. doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.06.004

Pluviano, S., Watt, C., & Della Sala, S. (2017). Misinformation lingers in memory: Failure of three pro-vaccination strategies. PLoS ONE. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181640

Tannenbaum, M. B., Hepler, J., Zimmerman, R. S., Saul, L., Jacobs, S., Wilson, K., & Albarracín, D. (2015). Appealing to Fear: A Meta-Analysis of Fear Appeal Effectiveness and Theories. Psychological Bulletin. doi.org/10.1037/a0039729

Haglin, K. (2017). The limitations of the backfire effect. Research and Politics. doi.org/10.1177/2053168017716547

Chakravarty, D., Dasgupta, S., & Roy, J. (2013). Rebound effect: How much to worry? In Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.03.001

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge