The quadrivium (plural: quadrivia) is the four subjects, or arts, taught after teaching the trivium. The word is Latin, meaning four ways, and its use for the four subjects has been attributed to Boethius or Cassiodorus in the 6th century. Together, the trivium and the quadrivium comprised the seven liberal arts (based on thinking skills), as distinguished from the practical arts (such as medicine and architecture).

Etymologically, the Latin word trivium means “the place where three roads meet” (tri + via); hence, the subjects of the trivium are the foundation for the quadrivium, the upper division of the medieval education in the liberal arts, which comprised arithmetic (number), geometry (number in space), music (number in time), and astronomy (number in space and time). Educationally, the trivium and the quadrivium imparted to the student the seven liberal arts of classical antiquity.[1]

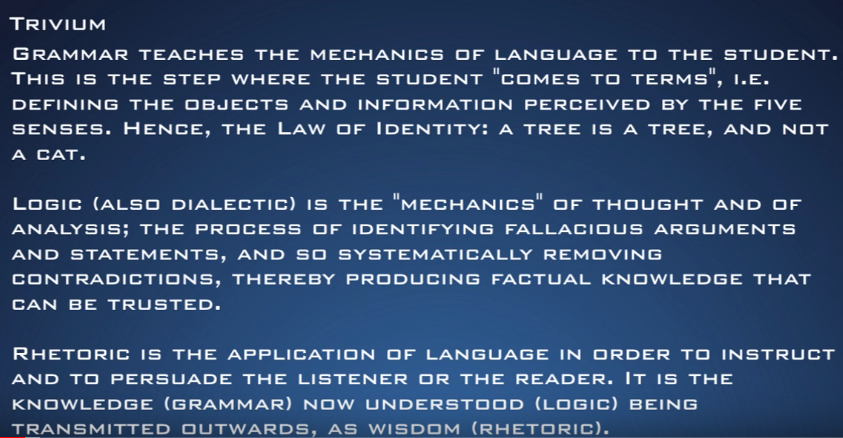

Grammar teaches the mechanics of language to the student. This is the step where the student “comes to terms,” defining the objects and information perceived by the five senses. Hence, the Law of Identity: a tree is a tree, and not a cat.

Logic (also dialectic) is the “mechanics” of thought and of analysis, the process of identifying fallacious arguments and statements and so systematically removing contradictions, thereby producing factual knowledge that can be trusted.

Rhetoric is the application of language in order to instruct and to persuade the listener and the reader. It is the knowledge (grammar) now understood (logic) and being transmitted outwards as wisdom (rhetoric).

One can utilise a computer analogy to conceptually explain the Trivium. Per analogiam, input (via input channels such as the senses/sensors, or any other form of information transmission ) refers to grammar, processing to logic (thought & analysis), and output to rhetoric (written words & spoken language).

Sister Miriam Joseph, in The Trivium: The Liberal Arts of Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric (2002), described the trivium as follows:

Grammar is the art of inventing symbols and combining them to express thought; logic is the art of thinking; and rhetoric is the art of communicating thought from one mind to another, the adaptation of language to circumstance.

. . .

Grammar is concerned with the thing as-it-is-symbolized. Logic is concerned with the thing as-it-is-known. Rhetoric is concerned with the thing as-it-is-communicated.[4]

John Ayto wrote in the Dictionary of Word Origins (1990) that study of the trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) was requisite preparation for study of the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy). For the medieval student, the trivium was the curricular beginning of the acquisition of the seven liberal arts; as such, it was the principal undergraduate course of study. The word trivial arose from the contrast between the simpler trivium and the more difficult quadrivium.[5]

Quadrivium

The quadrivium consisted of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. These followed the preparatory work of the trivium, consisting of grammar, logic, and rhetoric. In turn, the quadrivium was considered preparatory work for the study of philosophy (sometimes called the “liberal art par excellence”)[5] and theology.

These four studies compose the secondary part of the curriculum outlined by Plato in The Republic and are described in the seventh book of that work (in the order Arithmetic, Geometry, Astronomy, Music). [4] The quadrivium is implicit in early Pythagorean writings and in the De nuptiis of Martianus Capella, although the term quadrivium was not used until Boethius, early in the sixth century.[6] As Proclus wrote:

The Pythagoreans considered all mathematical science to be divided into four parts: one half they marked off as concerned with quantity, the other half with magnitude; and each of these they posited as twofold. A quantity can be considered in regard to its character by itself or in its relation to another quantity, magnitudes as either stationary or in motion. Arithmetic, then, studies quantities as such, music the relations between quantities, geometry magnitude at rest, spherics [astronomy] magnitude inherently moving.[7]

Medieval usage

At many medieval universities, this would have been the course leading to the degree of Master of Arts (after the BA). After the MA, the student could enter for bachelor’s degrees of the higher faculties (Theology, Medicine or Law). To this day, some of the postgraduate degree courses lead to the degree of Bachelor (the B.Phil and B.Litt. degrees are examples in the field of philosophy).

The study was eclectic, approaching the philosophical objectives sought by considering it from each aspect of the quadrivium within the general structure demonstrated by Proclus (AD 412–485), namely arithmetic and music on the one hand[8] and geometry and cosmology on the other.[9]

The subject of music within the quadrivium was originally the classical subject of harmonics, in particular the study of the proportions between the musical intervals created by the division of a monochord. A relationship to music as actually practised was not part of this study, but the framework of classical harmonics would substantially influence the content and structure of music theory as practised in both European and Islamic cultures.

Modern usage

In modern applications of the liberal arts as curriculum in colleges or universities, the quadrivium may be considered to be the study of number and its relationship to space or time: arithmetic was pure number, geometry was number in space, music was number in time, and astronomy was number in space and time. Morris Kline classified the four elements of the quadrivium as pure (arithmetic), stationary (geometry), moving (astronomy), and applied (music) number.[10]

This schema is sometimes referred to as “classical education”, but it is more accurately a development of the 12th- and 13th-century Renaissance with recovered classical elements, rather than an organic growth from the educational systems of antiquity. The term continues to be used by the Classical education movement and at the independent Oundle School, in the United Kingdom.[11]

see also: www.oundleschool.org.uk/Trivium-and-Quadrivium

Further References

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1177/0270467603251296

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Show/hide publication abstract

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1177/0539018412437099

DOI URL

directSciHub download