The biophilia hypothesis also called BET suggests that humans possess an innate tendency to seek connections with nature and other forms of life.[1] Edward O. Wilson introduced and popularized the hypothesis in his book, Biophilia (1984).[2] He defines biophilia as “the urge to affiliate with other forms of life”.[3]

Love of living systems

The term “biophilia” means “love of life or living systems.” It was first used by Erich Fromm to describe a psychological orientation of being attracted to all that is alive and vital.[4] Wilson uses the term in the same sense when he suggests that biophilia describes “the connections that human beings subconsciously seek with the rest of life.” He proposed the possibility that the deep affiliations humans have with other life forms and nature as a whole are rooted in our biology. Unlike phobias, which are the aversions and fears that people have of things in their environment, philias are the attractions and positive feelings that people have toward organisms, species, habitats, processes and objects in their natural surroundings. Although named by Fromm, the concept of biophilia has been proposed and defined many times over. Aristotle was one of many to put forward a concept that could be summarized as “love of life”. Diving into the term philia, or friendship, Aristotle evokes the idea of reciprocity and how friendships are beneficial to both parties in more than just one way, but especially in the way of happiness.[5]

In the book Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations edited by Peter Kahn and Stephen Kellert,[6] the importance of animals, especially those with which a child can develop a nurturing relationship, is emphasized particularly for early and middle childhood. Chapter 7 of the same book reports on the help that animals can provide to children with autistic-spectrum disorders.[7]

Product of biological evolution

Human preferences toward things in nature, while refined through experience and culture, are hypothetically the product of biological evolution. For example, adult mammals (especially humans) are generally attracted to baby mammal faces and find them appealing across species. The large eyes and small features of any young mammal face are far more appealing than those of the mature adults.

Similarly, the hypothesis helps explain why ordinary people care for and sometimes risk their lives to save domestic and wild animals, and keep plants and flowers in and around their homes. In other words, our natural love for life helps sustain life.

Very often, flowers also indicate potential for food later. Most fruits start their development as flowers. For our ancestors, it was crucial to spot, detect and remember the plants that would later provide nutrition.

Biophilia and conservation

Because of our technological advancements and more time spent inside buildings and cars, it is argued that the lack of biophilic activities and time spent in nature may be strengthening the disconnect of humans from nature. Although, it also has shown strong urges among people to reconnect with nature. The concern for a lack of connection with the rest of nature outside of us, is that a stronger disregard for other plants, animals and less appealing wild areas could lead to further ecosystem degradation and species loss. Therefore, reestablishing a connection with nature has become more important in the field of conservation.[8][better source needed] Examples would be more available green spaces in and around cities, more classes that revolve around nature and implementing smart design for greener cities that integrate ecosystems into them such as biophilic cities. These cities can also become part of wildlife corridors to help with migrational and territorial needs of other animals.[9]

Development

The hypothesis has since been developed as part of theories of evolutionary psychology in the book The Biophilia Hypothesis edited by Stephen R. Kellert and Edward O. Wilson[10] and by Lynn Margulis. Also, Stephen Kellert’s work seeks to determine common human responses to perceptions of, and ideas about, plants and animals, and to explain them in terms of the conditions of human evolution.

Biophilic design

In architecture, biophilic design is a sustainable design strategy that incorporates reconnecting people with the natural environment. It may be seen as a necessary complement to green architecture, which decreases the environmental impact of the built world but does not address human reconnection with the natural world.[11] Caperna and Serafini[12] define biophilic as that kind of architecture, which is able to supply our inborn need of connection to life and to the vital processes. According to Caperna and Serafini,[13] Biophilic architecture is characterized by the following elements: i) the naturalistic dimension; (ii) the Wholeness [14] of the site, that is, “the basic structure of the place”; (iii) the “geometric coherency”, that is, the physical space must have such a geometrical configuration able to exalt the connections human dimension and built and natural environments. Similarly, biophilic space has been defined as the environment that strengthens life and supports the sociological and psychological components,[15][16] or, in other words, it is able to:[17] (i) unburden our cognitive system, supporting it in collecting and recognizing more information in the quickest and most efficient way; (ii) foster the optimum of our sensorial system in terms of neuro-motorial influence, avoiding both the depressive and the exciting effects; (iii) induce a strengthening in emotive and biological terms at a neural level; (iv) support, according to the many clinical evidences, the neuro-endocryne and immunological system, especially for those people who are in bad physical condition.

Having a window looking out to plants is also claimed to help speed up the healing process of patients in hospitals.[18] Similarly, having plants in the same room as patients in hospitals also speeds up their healing process.[19]

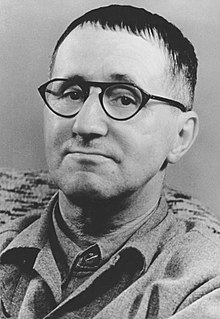

From 1930 onwards, Brecht became part of a wider complex of projects exploring the role of intellectuals (or “Tuis” as he called them) in a capitalist society. A Tui is an intellectual who sells his or her abilities and opinions as a commodity in the marketplace or who uses them to support the dominant ideology of an oppressive society. ] The German modernist theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht invented the term and used it in a range of critical and creative projects, including the material that he developed in the mid-1930s for his so-called Tui-Novel—an unfinished satire on intellectuals in the German Empire and Weimar Republic—and his epic comedy from the early 1950s, Turandot or the Whitewashers’ Congress. The word is a neologism that results from the acronym of a word play on “intellectual” (“Tellekt-Ual-In”).

From 1930 onwards, Brecht became part of a wider complex of projects exploring the role of intellectuals (or “Tuis” as he called them) in a capitalist society. A Tui is an intellectual who sells his or her abilities and opinions as a commodity in the marketplace or who uses them to support the dominant ideology of an oppressive society. ] The German modernist theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht invented the term and used it in a range of critical and creative projects, including the material that he developed in the mid-1930s for his so-called Tui-Novel—an unfinished satire on intellectuals in the German Empire and Weimar Republic—and his epic comedy from the early 1950s, Turandot or the Whitewashers’ Congress. The word is a neologism that results from the acronym of a word play on “intellectual” (“Tellekt-Ual-In”).